How You Make Decisions Shapes How People Experience Your Community

Are you a community or a club? A community or a dictatorship?

How your group makes decisions shapes how people experience your community.

Decision-making is required because we don’t all agree, or there are competing good outcomes that are mutually exclusive (move to X neighborhood or move to Y neighborhood?), or there are tough choices where each choice has some drawbacks.

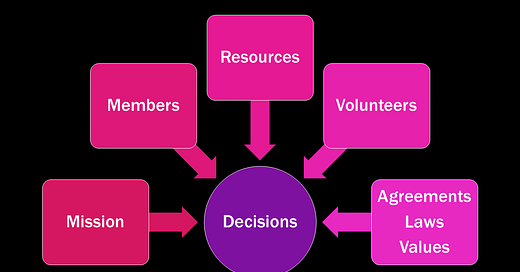

Decisions balance the group’s mission with the impact on its members and stakeholders, the resources that are available or could be found, volunteer time priorities, and agreements, laws, and values that need to be considered.

What is the mission of this group? How will this decision further or obstruct us in moving in the direction of our mission?

What is the effect on members of the group? Members now, and members in the future? What is the effect on stakeholders in the group who aren’t members? (Examples of stakeholders would be other people and organizations with which your group interacts. Building renters, for instance, or those who attend events, or those you serve free lunch to, etc.)

What is the effect on resources? What resources are needed to produce the desired result, and where will they come from? How might the desired result add to resources or be more efficient in use of resources? (Include in resources consumed or saved the expenditure of time of paid staff people.)

What is the effect on volunteers? What time investment is expected, and is that reasonable? Do volunteers need to have training? Will they end up feeling energized and fulfilled, or drained and depressed, by the decision you make?

What agreements are involved? Is the decision within the scope of the responsibility of a subgroup making the decision, and does it fit within the policies of the board or group as a whole? What laws are involved? What values? What will be the impact of this decision on those?

Successful decision-making in values-based groups like progressive religious or humanist groups has two purposes, in managing these factors:

Success in accomplishing the task and work in ways that help the group survive, at least, and thrive, at best — this is the outward purpose of the decision-making.

Bringing out the best in people and relationships — as a values-based group, this is the underlying inner or ethical purpose in all decision-making.

You can be successful in accomplishing the tasks and work themselves, but if you do not bring out the best in the people and build “right relationships,” the group will fail to fulfill its mission.

The opposite is also true: respecting the people and relationships at the expense of doing the tasks and work that need to be done, will end up sacrificing the group, because it cannot survive or thrive without accomplishing the work.

If we look at concern for accomplishment and concern for people as two different scales in a two-dimensional grid, and then look at the kinds of decisions we make at some key points in that grid, we end up with something like this illustration. (I’ve adapted this grid from the Black and Mouton Management Grid theory.)

Avoid: In the lower left corner, we see what happens in groups that have little concern for either accomplishment or people: such groups simply avoid making decisions.

A group with uses this as a dominant style of decision-making is an impoverished group. Not much will happen. People won’t feel good about belonging, and work won’t get done. Such groups don’t last long.

Avoidance style for decisions can work if the decision is not important to accomplishing the mission, or not important to the people involved. Have you been in a group where there was a lot of time spent on trivial decisions that didn’t matter to many people and that didn’t really affect the mission? It’s better to avoid such decisions than to bore the group so they have little patience for decision-making when it comes to big decisions.

But do remember that trivial to you isn’t necessarily trivial to others. People-concern includes empathy and respect for those who care about the decision.

Accommodate: A high concern for people and a low concern for accomplishment is called accommodation, because accommodating the wishes of individuals is more important than accomplishing the tasks or work.

Groups with use accommodation as the dominant decision-making style won’t get much work done to accomplish their mission. It will feel more like a club than a community. And though it has a high people-concern, it won’t meet the needs of either the group itself or some individuals within the group to accomplish the mission of the group.

Occasional use of accommodation style can be healthy, when the decision to be made has little impact on the mission or resources, but has a high impact on the group’s relationships. An example might be stopping the meeting’s regular agenda when someone uses what another participant considers a personal insult. Not dealing with that effectively, and quickly, communicates a low concern for people, and will make it harder if not impossible to work together. (There’s a reason that Roberts’ Rules puts a high priority on points of personal privilege, used when someone experiences an insult, whether intended or not.)

Command: If a group has a high concern for accomplishment, and little concern for people, decisions will tend to be made command-style. The board or a president or a staff executive makes decisions, and expects others to carry them out, with little involvement of the people carrying out the decisions or the people affected. (The person making the decision may believe they are concerned about people, in making a decision they deem best, but there is no process to check whether their belief is accurate.)

Those belonging to a group that habitually uses command-style decisions may experience it as a kind of dictatorship, where their individuality, ideas, and expertise aren’t respected unless they’re in the command position. They’ll feel irrelevant and drift away fairly quickly. And/or, your group will attract people who love to command others — which in a group focused on the worth and dignity of people means you’ll lose those who find your group to be hypocritical. You’ll end up with a group with a few people comfortable with giving orders and others comfortable with taking them — and you’ll lose those who aren’t comfortable with either position. In a group that values human worth and dignity, a command style can be perceived and often is one that prioritizes accomplishment over the dignity of those doing the work or affected by it, so it is essentially contrary to the group’s mission.

Those using a command style may believe it accomplishes tasks and work better, but (as in the discussion above of perceived insults in a meeting) when the relationships or individuals experience hurt, it will be more difficult to work together. Plus the command style tends to ignore some people who may have expertise that would be helpful, either in warning against bad decisions or in improving the decision.

A command style is occasionally healthy, if the person or subgroup making the commands has accurate information and time is of the essence. The best example is when a fire alarm goes off during a meeting. Those with expertise about how to respond can issue commands like “we’re evacuating now” — and it is out of ultimate respect and care for people that they do so!

A command style can also be healthy when there is a clear mandate to delegate a decision. For instance, a community that owns a building might delegate to a subgroup the decision on what color to paint the bathrooms, trusting that they will use within the subgroup a more inclusive decision-making style, but will “command” it for the rest of the group. Staff members answering mail don’t check every decision about how to answer inquiries with the entire group membership. Delegation is a kind of controlled, trusted “command” decision-making. Clear communication on the scope of authority to make such decisions is crucial to success in delegating decisions to an individual or subgroup.

Sometimes, we try to balance concern for people and concern for accomplishment by compromise. In decision-making by compromise, everyone trades off a bit of what they believe is the right decision, to try to come to some decision that includes a bit of each proposal.

A group that operates mostly by compromise will be seen as a status-quo group. Transformational and adaptive change is almost impossible.

Surprisingly, compromise is often the least effective decision-making strategy. By compromising, the group may not work towards a creative solution that meets more needs of both people and task. Everyone wins a little, but everyone loses a little, too, and that can feel as badly as not winning anything. Plus, the solution may, because it is simply parts of what everyone wants, not be effective in accomplishing the task.

Compromise doesn’t work when the different proposals are mutually exclusive. If some people really are invested in having a blue bathroom, and others in wanting a yellow bathroom, for a trivial example, nobody is likely to be satisfied with a green bathroom, though that is an obvious “compromise.” Similarly, if two different time-tested models for long range planning are proposed, it is usually not helpful to simply try to incorporate the strengths of both models, as you’ll end up with a third model that is not tested. (It is, however, not really compromise to ask what needs are not met in model A or in model B, and see how those NEEDS can be met better in making the choice of either A or B.)

Compromise can work when time is short and something needs to happen right away, and there is an agreement to revisit and reshape the decision to make sure that it is working and that people are satisfied with the choice.

Compromise can also work on those decisions when people care more about getting something to happen than about the particulars.

Collaboration is one name for the decision-making model where everyone works together to come up with a solution that (a) everyone agrees will likely work to accomplish the goal, and (b) everyone feels was chosen with care and respect to the needs of both those involved in the decision-making, and those affected by the decision.

Groups which habitually use collaboration (and when choosing not to, do so carefully) are experienced more as community.

Collaboration is where creative problem-solving really happens. When there are significant initial differences among the decision-makers, the proposal agreed on at the end likely won’t look much like what anyone initially endorsed.

Collaboration takes time, and isn’t always fully possible. If there are people unwilling to fully participate in the collaboration process, it won’t work. For instance, if someone says “no” to another proposal, true collaboration would be that they would also be committed to a process where that “no” was also tentative unless everyone ends up agreeing with them after a respectful discussion. Simply saying “no” (or “yes” to something that others say “no” to) and not working towards agreement on your stance, is not collaboration, but is more like Avoid or Command or Status Quo.

Collaboration works best on decisions where there all or most participants are willing to be creative and adopt a choice that they did not initially endorse.

Collaborating on less critical decisions can build the trusting relationships that make it possible to collaborate on crucial decisions. If the tendency is to ignore either people or accomplishment on smaller decisions routinely, then collaboration will be difficult on crucial decisions.

Using collaboration on trivial decisions (where the effect on accomplishment and people isn’t very high) can be boring to participants, and feel like a waste of time — and thus itself disrespect the people involved, both as people concerns and as concern for moving on to more important tasks.

Collaboration when there is limited expertise or time can be counter-productive. You do not have to be bound by consensus decision-making in figuring out how to evacuate a building during a fire, for instance. Or it might take your group so much time to come to a decision that the moment of opportunity is lost (hiring a candidate for a staff position, for instance — they may have found another position before you get consensus). And, not using collaboration because of limited time usually means some tending to the relationship/people side of your concerns after.

Decision-making can be especially difficult in times of culture change. (And when are we NOT in a time of culture change???) Using collaboration in a rigid way (waiting for enthusiastic agreement by all) can mean that the slowest learners and adapters rule.b

For instance, if everyone currently in the group only can tolerate music that was popular in their teen and adult years, or only one genre of music, then there is little likelihood that the group will be inclusive of different age groups, no matter how much they want to “have more young people.” But merely bringing in a new kind of music without bridging that in some way for those unfamiliar with it will have all the negatives of compromise — nobody ends up happy (the older people because they don’t “get it” and the younger people because they can see the older people don’t really like their music and aren’t trying to understand it).

Music, like other cultural choices, is not a trivial decision. Music is often a key to building relationships and connections, appealing to the emotions and memory and even identity, and not just the cognitive rational side of our personhood. Rigidly expecting others to appreciate “your” music rarely works. Music is an experience, and finding music where everyone can feel a part of that experience is a challenge, but one that illustrates these decision-making processes well.

An impoverished organization (low people, low task) might decide not to use any music, as it’s too hard to figure out good choices.

A club organization (high people, low task) will look for music that people love already, whether it’s appropriate for the topic or reaches people deemed “outsiders.” (Club organizations think they are people-oriented, but that people-orientation tends to be just about those who belong, and often just about those who’ve belonged for a long time.)

A dictatorship organization (high task, low people) will decide what music should be used and not care if anyone as a person likes it or not. “We SHOULD have more rap music to attract a different audience, so here it is” with no consideration for introducing it to those who are unfamiliar with the style, or even seeing if fans of rap music think that piece is appropriate right now.

A status quo organization will compromise (mid task, mid people). Playing music from different styles within the same meeting, without “bridging” to help people connect to ones they aren’t familiar with, will feel random and chaotic to everyone.

A community (high task, high people) will both take the temperature of who is there and who the group wants to include and isn’t there now, and also take seriously helping people to see the best in each style. And continuing to grow and experiment and expand what is “our music” together. This isn’t easy. It may mean finding the rap music piece that has lyrics that can be heard clearly by those who are older and harder of hearing, and that has a message those older people will resonate with. It may mean finding a folk music piece performed by a more recent artist with a different sense of rhythm than the folk fan grew up with.

Once, in a talk about economic justice I addressed the assumption that people should just be able to “get a job.” The group was one where the message would resonate with all but where tastes in music were very different. So I used the song “Get a Job” — a country piece — performed in a classical music style. Everyone got it, and everyone laughed — there was a real sense of community in that experience. I never used it again, as it wouldn’t have been thematically appropriate in other contexts, but it did the job that day.

And one time, there was an accidental experiment with one group that was pretty age and racially diverse. During an informal picnic, someone started playing their phone’s playlist over the speakers, then got called away. The phone’s playlists continued from one to the next. The person had very eclectic tastes in music. I watched body language. I noticed that when more traditional music came on, younger folks tightened their bodies subconsciously and even moved away from the source of the music. Older people’s bodies moved rhythmically to the music. And when hip hop came on, some older folks tightened their bodies subconsciously and moved their bodies away. And younger bodies were clearly moving to the music. Even the Beatles who have appealed to several generations obviously didn’t appeal experientially to everyone. Everyone was responding physically to the music as they were talking to others, the body language was all pretty automatic. Then a playlist of Motown came on. For that group, it was clear that the universal music was Motown. Everyone was moving to the music, and smiling, some humming along, even as they continued their conversations and moving to get food or talk to others. It wasn’t often practical to actually use Motown music in future planning (having words that promote the theme of the program is another consideration), but we tried to consider that rhythm and style in making selections.

I do believe — and the title of my Substack says it — that community matters. Finding ways to make decisions more collaboratively more of the time is crucial. Sometimes that’s through formal process. Sometimes that’s through those making decisions being attuned to what people want, doing a lot of asking and listening, and having expertise to judge what’s an effective way to get things done.

Organizations that thrive in the long run function fundamentally on the community/collaboration model of decision-making. They’re concerned to hear from everyone, to let the diversity of the group shape unique solutions that might not have been the preference initially of anyone — and thus those within the group continue to be transformed by their experience, as well as contribute to it. The group accomplishes goals in support of its mission, and also those within find more of their better selves being expressed.

Decision-making styles influence whether your group achieves community or remains a club, a group where a few control and the rest follow, a do-nothing group that doesn’t satisfy, or a group that doesn’t grow and change much in response to inside and outside challenges and opportunities.

You may think you’re making a choice whether to pick this or that project to do, or what space to rent — you are also making a choice about what kind of group you want to be.